A couple months ago before the start of university, I sat down with my dad for what he described as “financial planning.” In less bespoke terms, we talked about how much money I wanted to make post graduation. Or, more accurately, how much money I needed to make post graduation so that I could afford the lifestyle I wanted.

(I think this was actually his sneaky way of getting me to not go into city planning, which is what it wanted to pursue at the time. Well, his plan worked).

We were chugging along and I was feeling pretty good about things.

Until we got to housing.

The average house in the City of Toronto costs 1.25 million right now. Under current market conditions, that would make my mortgage payment more than $7 000 a month. Using the rule of thumb that housing is roughly 1/3 of your total income, that means I would need to make $261 000 per year if I wanted to own a house in this city.

Not happening anytime soon.

A little bit dismayed, but still somewhat hopeful, we repeated this process several more times, trying to find places where I could afford to live.

In case you had not guessed, it went downhill very fast.

On a $75 000 salary (which is already quite ambitious for a new grad in a non computer science field), I can afford… *checks notes* this piece of vacant land in Clarington, measuring 44 x 72 feet.

Vacant. Land. In Clarington.

Where on earth even is Clarington?

If you go to its Wikipedia page and scroll to the attractions section, the first thing you see is that it “has more Santa Claus/Christmas parades than any other town-sized municipality in Canada.”

Great. While sitting on my vacant, houseless lot, I will be able to watch a fictional character yell at and probably traumatize young children.

So yeah, the housing situation, it is bad.

For young people like me (and if you are reading this, probably you as well), this crisis is more than just vague words on a news headlines. It is a reality we have to confront head on. Which is a really nice way of saying, “we’re fucked. lmao.” Like many in this country, I have accepted that I am probably not going to be able to afford my own home for a long time after graduation. And even when I do, it will be some shack in a far flung suburb - not exactly a dream property, and definitely not what previous generations had to settle for.

The implications of this crisis, however, go far beyond the personal level.

Increasingly, immigrants are choosing not to come to Canada because housing is so expensive. Does that mean we will have an immigrant shortage? Probably not any time soon. Desire to come here still far exceeds placement spots. But it does mean that if this continues, the pool of immigrants we have to select from shrinks, and so our country will miss out on some top talent.

Furthermore, these high costs lead to a lot of money getting tied up in real estate. Investors choose to buy homes over other things because their value just keeps going up. For everyday people, they have less of a choice - if they do not fork over these funds, well, then they end up on the streets.

The issue is, housing is a fundamentally unproductive investment. When money is invested in something like stocks, it means companies can use these funds to invest in technology, develop new products, or hire more workers. When it is saved in banks, they can loan it out to other people or firms who then use it to finance various different productive activities. Or, when it is spent directly by consumers on goods and services, it increases company revenues, allowing them to expand and grow. No matter where it goes, that money is actively circulating through the economy, helping businesses grow and people succeed. But when you put all the money in housing, the value just sits there until you sell the home. No economic activity happens, and no one else is able to benefit from your investment.

That may seem like no big deal, but it actually is kind of a big deal. In fact, it is one of the key reasons why Canadian economic productivity per capita has fallen far behind that of almost every single G7 peer nation in recent years.

All this is to say, high housing prices kind of suck.

So, why is housing so expensive? Well, it is complicated.

First thing crucial to understand is that the housing market is really like the market for any other good. There is supply of housing, and demand for it. Each side of the equation plays in role in determining how many homes are on the market, and for what price they can be bought out.

Given that it tends to get most of the media attention, lets start with demand. Investors, especially international ones, are snatching up homes like crazy. To make matters worse, they usually are not renting them out or anything like that. Rather, the homes just sit empty. For these millionaire foreigners, it is a massive hassle for them to actually pay a broker, find someone who is willing to rent the home, manage the rental process, etc. In their minds, the paltry rent revenue they could otherwise collect is simply not worth it, especially compared to the other benefits they derive.

What benefits, you ask? Well, for one, the massive increase in home value. Then there are those who are simply looking for a place to keep their assets because the financial systems in their home countries’ are unstable. Others just need a Canadian address for tax or business purposes. And then these are people who use these investments as a cover for illegal activity. I kid you not - the housing market, especially on the West Coast, plays home to one of the largest money laundering operations in the world.

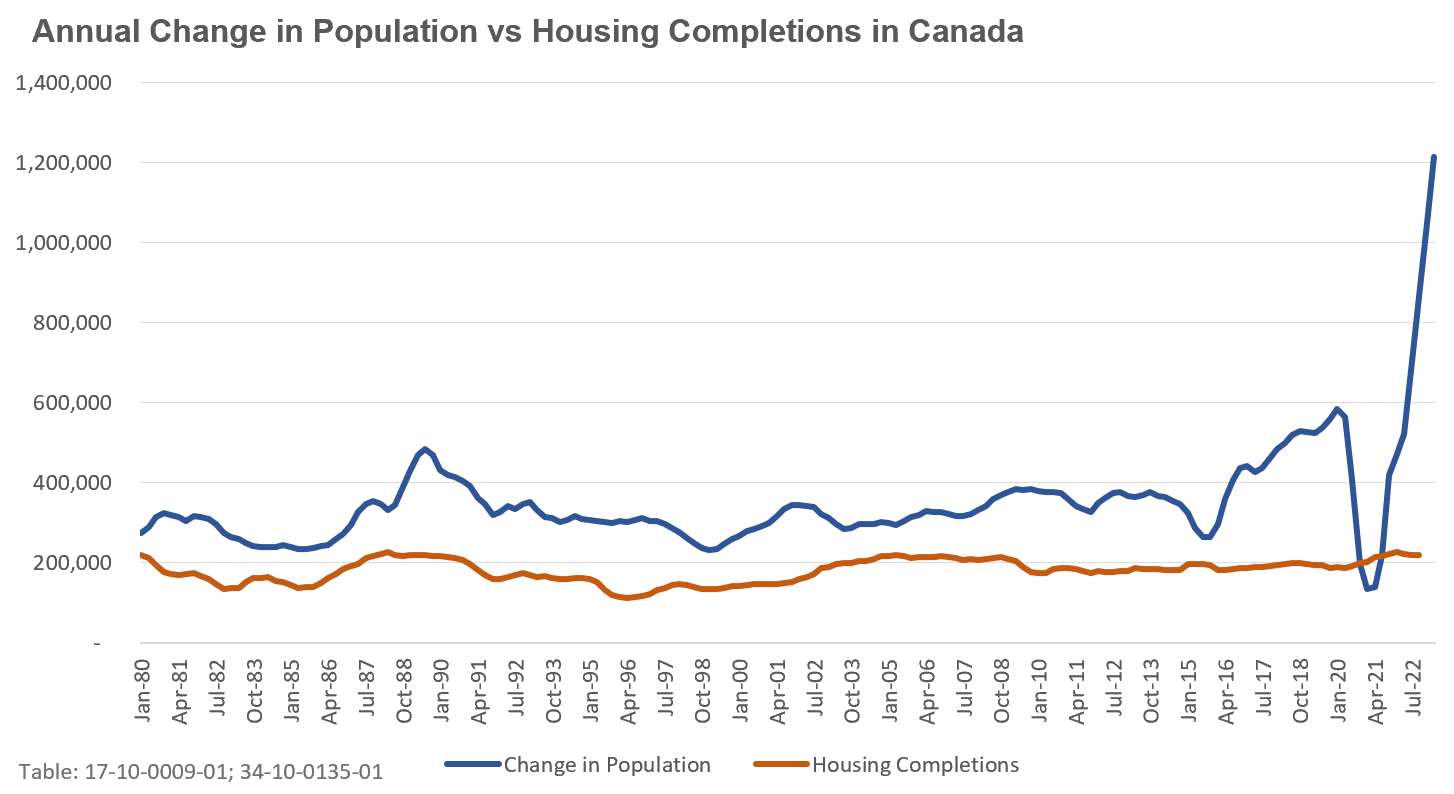

We also can not talk about housing without touching on Canada’s growing population. Immigration is on the rise - we are on track to admit 500,000 new immigrants annually by 2025. That is akin to adding a new Halifax every year. Immigration rates in Canada are by far higher than any other developed nation in the world

This in and of itself is not problematic. In fact, Canada desperately needs immigrants. Our population is aging, and we do not have enough working aged people to keep the economy going or to support the pensions of those who are now nearing retirement age. In a well functioning, free market, if demand for housing were to increase, over time, supply would be able to keep up.

But that has not happened. And so, we can say that most of the problems lie on the supply side.

Building housing is expensive. Really expensive. Usually, developers rely on financing from banks in order to cover a lot of the upfront costs, but the degree to which they can access this credit is dependent on interest rates. If interest rates become too high, then builders will decide to simply stop building. This, in fact, is what we are seeing now in Ontario.

The same is true for other costs, like materials or labor. In Canada, we currently have a massive shortage of workers in the trades (e.g. woodworkers, electricians…) that is only expected to get worse. If construction companies can not find people to build the homes, well, then no homes are getting built. And even for projects that do end up proceeding, they face significantly higher costs which inevitably get passed onto buyers.

But wait. That is only the beginning.

In most developed countries (including Canada), real estate has always comprised a big part of people’s retirement savings. When you are young, you buy a house. You live in it with your family, and over time you pay off the mortgage. Then, as your kids grow older and move out, and as you near retirement age, you do not need so much space anymore. So, you sell your big home and buy a smaller one instead. The surplus value of the original home then becomes your retirement fund.

For the longest time, this model seemed to work. After all, housing is supposed to be a fairly stable investment. The number of people is increasing, but the amount of land stays the same. So, housing prices keep (for the most part) going up. And as they do, the value of homeowners’ retirement funds grows. All is well.

Unless you are a young person.

You see, the problem is that the retirements of millions of people are now dependent on housing prices not only going up, but also staying up.

What this means then, is politicians do not want to do anything more than pay lip service to the housing affordability issue, because if housing prices really were to come down, it would spell doom for virtually every middle aged or older adult who’s life savings are in the value of their home.

So, housing prices stay high. Unlucky for us, I guess.

Another thing we have to talk about is NIMBYism, also known as ‘Not In My Backyard.’ NIMBYs are local property owners and residents who oppose housing (and other types of) developments in their local communities. To be honest, they have good reason to do so. More homes means more people, which means more noise, more traffic, more crime, more crowding, etc. Not to mention all the disruption that prolonged construction brings.

All this means, whenever a new housing project is proposed, they push back. Hard.

Compounding the problem is that generally, it is local politicians who get to decide if a housing development is approved. This makes them more sensitive to the concerns of a specific group of local residents (read: NIMBYs) as opposed to broader societal welfare. If 500 people oppose the new apartment building down the street, the federal MP who represents 150,000 constituents probably does not care, but the city councilor who only has 10,000 constituents definitely will.

It would be amiss not to also mention the role that public consultation plays in this. Usually, whenever a new development or changes to zoning laws are proposed, planners will hold a series of meetings with local residents to discuss their concerns. But the people who show up at these meetings tend to be opposed to the new housing, because, well, they already have homes. They do not care about housing supply, they just want to protect the neighborhoods they already have.

The residents who would live in these proposed developments, on the other hand, they are not going to be at these meetings. Heck, they might not even yet be aware that this is where they will be moving into in five years, if the project gets approved.

The result of all this then, is that bureaucrats and politicians alike are put under a lot of pressure by a small but vocal majority to, wherever possible, prevent developers from building housing.

And this shows in government policy. Municipalities usually have the power to decide what type of housing can and can not be built where. And they do what is called “zoning,” a process by which they draw boundaries on a map and say that “this area is zoned only for detached homes.” “Here, you can build up to five floors.” Etc.

The problem is, because of chronic NIMBYism, almost all of our cities nationwide are zoned exclusively for single family detached homes. In fact, pretty much everywhere, it quite literally is illegal to build anything more than that. The only way new housing construction can occur then, is through the addition of single family homes on the outskirts of cities. This urban sprawl is not only incredibly bad urban planning (that is a rant for another time), it is also inefficient. In a world where land is becoming incredibly rare, and given that a condo building with 20+ units takes up the same place as 3 or 4 single family homes, we should be making room for the former.

In an ideal world at least. In reality, whenever anyone tries to make any change, local residents revolt and city governments cave in.

But it gets worse still. Lets talk about leftists.

Those on the political left generally tend to be skeptical of corporations. Prime among them are big developers and housing builders, who they view to be “evil” and “profiting off of a basic human right.”

Taken to the extreme, this argument says that any policy which supports building more homes, short of a total overhaul of the ‘capitalist system that has commodified what is a human right,’ should be rejected because all it does is enrich greedy developers.

Putting aside this lofty and unhelpful rhetoric, it is also simply not true.

Yes, developers make profit off of building housing. But this profit comes from, well, building housing. Besides, these advocates’ alternative of co-op or public housing simply is not scalable.

The point of non-profit housing options is that they offer housing below market price. Which usually entails taking a loss.

The thing is, someone has to make up that difference. Rather unsurprisingly, the only group that has the resources to do that is the government. And given that housing is so expensive, the costs for this subsidization rack up quickly.

Consider Trudeau’s recent announcement in London where he committed 75 million dollars! How exciting. That will build, over the next few years, 2 000 homes.

Between 2016 and 2021 (the most recent data available), London’s population grew by almost 40 000 people.

You see what I mean? This model simply does not work. The long term goal should be so that only those who really need it have to rely on public housing - people with disabilities, those transitioning out of the shelter system, new immigrants. etc. Everyone else should be able to afford some type of market rate housing.

This attitude of animosity towards developers is not just about optics. It has real consequences.

The best example of this is how municipal governments across Canada have taken advantage of the situation to impose a whole host of taxes on developers.

And when I say a whole host of taxes, I really do mean that. As in, on your average Toronto house, $186 000 worth of taxes.

And you know who ends up paying these taxes? You! (Ok fine, it is a little more complicated than that. We will get there in a second).

To be clear, I am not arguing that the sole reason development fees are so high is because of some angry leftists. But I think it does play a role, albeit a small one. The other consideration is just that cities want money and developers are an easy target.

Tldr; there are simply not enough places where it is both legally permissible and financially viable to build new homes. Ergo, housing shortage.

Well then, how do we fix all of this?

First off, reduce the fees. Municipalities need money, yes, but there are so many other ways to raise it - by increasing property taxes on luxury homes, introducing vacant homes taxes, hiking parking levy’s… the list goes on and on. Taxing the construction of a commodity that everyone needs is just cruel.

At this point, the discourse usually goes, “what’s to say developers won’t just take the lower taxes but keep the profits and not actually reduce prices?” But this misses the point. The way we bring down housing prices is by increasing supply. And even if the savings are not passed on directly, what the increased profits do is they incentivize developers to build more homes. Projects that previously did not make financial sense because of these additional $186 000 in costs per unit (which, for a large development, can add up to tens of millions of dollars) may now become more viable. And over time as a result, more housing gets built.

This also applies to affordable housing requirements. To be clear, there is nothing wrong them in moderation. They can be a powerful tool in the fight against displacement of local residents during redevelopments. But politicians, eager to look like they are standing up for the ‘little guy,’ go way overboard with them. If you force developers to sell too many units below market price, then at some point the project just does not make financial sense anymore.

Having only 10% affordable housing within a project may not be as good as having 20%. But it sure is a heck of a lot better than no new housing at all.

Second, change the zoning laws. Seriously. We should be able to build dense housing almost everywhere (I will save my little density rant for another time). People’s right to afford a home trumps your desire for a quiet leafy suburban street. If you really value your peace, move to Owen Sound or something.

And please, none of that “missing middle” (midrise buildings, usually 4-5 floors in height) nonsense. We can talk about having more “gentle density” later on when we are not in the middle of a housing crisis. Right now, we should just be building as tall as we can go. A 20 story building will contain way more homes than a five story one.

(There is an interesting tangent here on process oriented vs outcome oriented city planning, but that is a rant for another time.)

Maybe it is true that within cities, we are never going to get the political will to make these changes. Local governments are far too close to the ground to ever get over the cries of NIMBYs. Thankfully, we do not need to work with them. In Ontario (and in a lot of other places too), local governments exist merely as extensions of provincial ones. As in, Doug Ford could, under our current legal framework, literally abolish the City of Toronto tomorrow and have the province run all city government functions. That is how, for instance, in 2018, he was able to unilaterally cut the size of our city council from 47 councilors to 25.

It would be kind of cool if they used that power to compel cities to cut development charges and change zoning laws. You know. The important stuff.

Third, moving beyond a regulatory level, we need to make it cheaper to build homes. There are two main ways we should go about this:

To alleviate the shortage of workers in the skilled trades, more young people need to be encouraged to go into those fields by cutting apprenticeship fees and introducing mandatory relevant courses in high schools

To allow both for-profit and non-profit developers to build more, lower cost financing for the construction of new units should be provided

Fourth, on demand side solutions. Thus far, I have mostly focused on how we can tackle housing supply issues. After all, high housing prices in Canada are inherently a supply side issue. But in the short run, I think there is some benefit to demand side remedies as well. Most notably, restrictions on foreign nationals buying homes, and on how many homes people can actually own. In the long run, however, if housing prices stabilize, then there will not be much of a need for such measures - if prices no longer keep going up, then speculators will turn to other investment options and the problem will go away.

Next then, I want to talk about this from an equity lens. Advocates, understandably, have raised concerns about how housing development could exasperate social issues and challenges that we face. I disagree.

The most commonly heard complaint is on gentrification, which is when a previously poorer area gets redeveloped, so housing costs go up which forces the original residents out.

A couple issues with this claim. First, the alternative is to leave these people in these decrepit neighborhoods, living in old and poorly maintained buildings. It is unclear how that is any better. Second, the only reason that gentrification even exists is because housing is so expensive everywhere else. The notion that, if you are priced out of a community, it means you become unable to find anywhere new to live, this is a direct result of a lack of supply that drives prices up. In the short run, governments should probably step in with things like rent supports or subsidies so that local residents will be able to live in the same communities post-development with pre-development rents. In the long run, building more housing brings prices down everywhere, and the problem fixes itself.

Yes, this is even true with luxury housing. Let me explain.

When you build more expensive homes, the prices of that ‘class’ of homes goes down. So people who previously bought middle market properties can now afford luxury ones. When the demand for middle market homes falls, their prices also decrease. And this keeps cascading, as everyone moves up a bracket in the type of home that they can afford.

The end result, then, is even the lowest end housing becomes more affordable.

Housing discourse in this country often gets framed as a bunch of old, angry, fist shaking homeowners hellbent on destroying the dreams of young people. And while that is part of it, the real picture is so much more complicated.

Thankfully, there is reason to be hopeful. The political tides are changing, and perhaps, our leaders are finally recognizing that things cannot go on like this much longer.

Meet Sean Fraser. Canada’s new housing minister.

In several months, he has done more on lowering housing prices then every other politician over the last few years combined.

Most notably, he launched the housing accelerator fund, which basically gave local governments a ton of money on the condition that they loosen zoning laws and cut development fees. So far, cities, desperate for cash to plug their post-COVID budget holes, are buying in. Under this plan, he has signed agreements with several municipalities across Canada, with many more along the way. This initiative is still in its early stages, but the signals are promising.

Better yet, he is not the only one. Half the Twitter (you will never hear me call that site by its new name) videos Conservative leader Poilievre puts out these days are about changing zoning laws so we can build more homes. In Ontario, both the opposition New Democrats and basically non-existent Liberals have been calling on premier Doug Ford to do the same.

The fact that building housing in this country has become something all political parties agree on and something they are actively pushing each other to do more of, is incredible.

My brother Alex, he is a few years younger than me. I am sure that when he heads off to university, my dad will have the same financial planning conversation with him that he had with me.

And my hope is that their conversation will go differently. For one, he wants to go into STEM (read: he will probably have a higher salary during his internship then I will after working 20 years). But also, when they get to talking about housing, maybe he will not feel the same sense of hopelessness and despair I felt.

Maybe he will not have to deal with the prospect of living on a vacant lot in Clarington.

Maybe, by that point, we would have finally introduced some smart and sensible housing policy that has made housing more affordable for everyone.

Maybe by then, as a country, we will have realized.

We need to build more homes.

Image Sources (in order)

housesigma.com

https://www.movesmartly.com/articles/canadas-population-is-booming-while-housing-starts-tumble

https://twitter.com/yimbyaction/status/1553130764186910722/photo/1

I read a government published economics report awhile back and one of their suggestions to halt the housing crisis was"get consumers to live in multi-generational homes to decrease demand" 💀.

I think you really hit the nail on the head on this one; I just wonder if there ever will be the political willpower to do things like this. Even so-called progressive parties in places like BC have made little progress on addressing the housing crisis, and in other places like Ontario and Quebec the conservative parties seem to have a iron grip on rule that probably won't change within the next election cycle. Who knows, maybe Poilievre will solve the housing crisis (highly doubt it). I just can't help but think that there is so much capital interest in the housing market that it is unlikely to be solved. Maybe that's too cynical.

On the other hand, and I don't want to seem like I'm minimizing the housing crisis, I don't think that it's universal across Canada (it's probably most acute in the GTA and GVA). I think the Clarington example is maybe a bit cherry-picked. I know the 260k figure scared you from pursuing your dreams and I think that's an unfortunate reality. But you can afford a home in many places in Canada with a salary closer to 100k (source: https://www.ratehub.ca/blog/what-income-to-afford-home-canada/.) This is true even in Montreal, one of Canada's 3 major cities, where the average cost is 110k (although Mtl is getting less affordable). This is still not ideal as it's above the median income, but not everyone has to buy a home. It's probably cheaper to rent for a lot of people and renting isn't inherently worse as long as people get housing. I know that there are probably more opportunities in Toronto or Vancouver, or maybe you have familial or personal connections to Toronto or maybe even language barriers that prevent you from leaving. But at least on an individual basis (which I know obscures the point of this rant which is about structural issues), you have options where you don't need to strap yourself to a 200k job.

Edit: actually this is a bad 12 am take like I personally would never move to Alberta or the Maritimes no matter how cheap it was so that leaves your only options as Ottawa (ugh) or Montreal and otherwise the Clarington example is very real